Occupy Art?

Stange, Raimar, and Tal Beery. “Occupy Art?” Cura, no. 12, Autumn 2012, pp. 64–69.

Interview in English and Italian.

OCCUPY ART?

By Raimar Stange

“The way artists handle their art, where they make it, the chances they get to make it, how they are going to let it out and to whom – it’s all part of life style and a political situation”, pointed out already in 1973 Lucy R. Lippard, in her cult book Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972.

Since then, the political situation of the art industry has been going downhill because of the rising power of neoliberal and globalizing capitalism. Nowadays, the ones who call the tune in the world of art are the extremely rich collectors and a handful of gallery owners, already almost omnipotent, whose “career” increasingly sees them also become museum directors. In this context, we could say the art scene is split into two groups: one, by far the most conspicuous, complacently serves this decadent and self-referential industry in its own interest, while the other, much smaller group firmly refuses to continue to participate in the artistic production of saleable goods. By contrast, the artists belonging in the latter group challenge the structures of the system with their work. The group Occupy Museums, born in New York last year as part of the movement Occupy, belongs in this group. These artists ask for art to cease being a luxury item. It should instead be considered a necessary good, “the soul of the community.” “Art and culture for 99% of the people”, is one of their central claims.

Tal Beery interviewed by Raimar Stange joined Occupy Museums in 2011. In this conversation he speaks from his own perspective and does not intend to speak for the group as a whole.

Raimar Stange How would you describe and characterize the work of Occupy Museums in a few sentences?

Tal Beery Occupy Museums is an affinity group of the Occupy Wall Street movement, and intends to expose corruption in the art market, the degrading effects on culture of the financialization of art, and the effects of the corporate structure of museums on the commons. I believe we are interested in the creative flourishing of the 100% and in envisioning cultural institutions with more open, compassionate, and democratic processes and agendas. We strive to work within a horizontal consensus-based process, and our meetings and actions are open for anyone to join.

R.S. How did you get involved with Occupy Museums?

T.B. I am a good example of someone who became involved with Occupy Museums after participating in an inspiring action. This action was at Lincoln Center, and was held to commemorate the final performance of Philip Glass’s opera, Satyagraha, based on the life of Mahatma Gandhi. When I arrived at the Lincoln Center just before 10pm, the New York City police had already barricaded the entire courtyard. A public space I had visited throughout my life for countless shows was transformed into a militarized, threatening environment. Police spaced themselves throughout the courtyard and ensured only a slim walkway for performance patrons to exit, so scared they were of the one hundred or so peaceful activists gathering behind the barricades. This vision of state power gripping our city’s cultural institution was compounded by the fact that we gathered near the David H. Koch Theater, named after a tremendously wealthy donor who has spent hundreds of millions of dollars supporting policies that reduce taxes for the rich while cutting social services and the National Endowment for the Arts.

But the action progressed beautifully. As the opera audience were let out, some patrons came to join us from the other side of the barricades. The first to do so were brutally arrested, but eventually the pressure from the crowd overwhelmed the police and their presence behind the barricade was tolerated. We held a general assembly, where Phillip Glass read a magnificent text. Lou Reed joined as well and performed. It was truly amazing: one large group, together, divided only by a police barricade that was overtaken and dissolved by the group. I knew then that something important was happening here and I wanted to be a part of it. A few weeks later I attended my first Occupy Museums meeting and have been active since.

R.S. What do you see as the main difference between artists and activists?

T.B. Perhaps this question presupposes a false distinction. It is important that we recognize that in many cases today, the market plays a strong role in defining “art” and “the artist.” And in some ways, the distinction between art and activism only serves the interests of those who would like to de-fang and de-activate art. “Art” today is often situated within gallery walls that allow it to float weightlessly above the contemporary political context. Sometimes I believe that things are called “Art” only when they are safe and politically ineffective. I think this is a product of a system that requires artists to seek wealthy collectors who have a vested interest in maintaining their power. I have seen politically engaged artists create work that is highly valued, subsumed by market forces, and consequently hung in the homes as a sort of trophy, the spoils of another vanquished foe. On the other hand, it is possible that the drive to conflate the two serves to de-activate activism, making otherwise subversive activities acceptable within a “safe” arts context. To oppose this, we must weaken the role of the market in the arts and in our culture. In Occupy Museums, I believe we self-consciously do activism within the art world, and not art within the activism world. Both artists and activists perform symbolic actions to make statements. Are the methods employed by artists to communicate ideas so different from those used by activists? Is the content communicated by artwork necessarily so different from that communicated by public political action? Where do we draw lines? I don’t intend to suggest that we should do away with all distinctions, only that these boundaries need to be examined, tested, and sometimes pushed. Especially today, in an age of overwhelming market dominance, we must ask whether and how our culture reflects and is limited by capitalist ideologies.

R.S. Why is it interesting for the Occupy Movement to work in the context of the 7th Berlin Biennale?

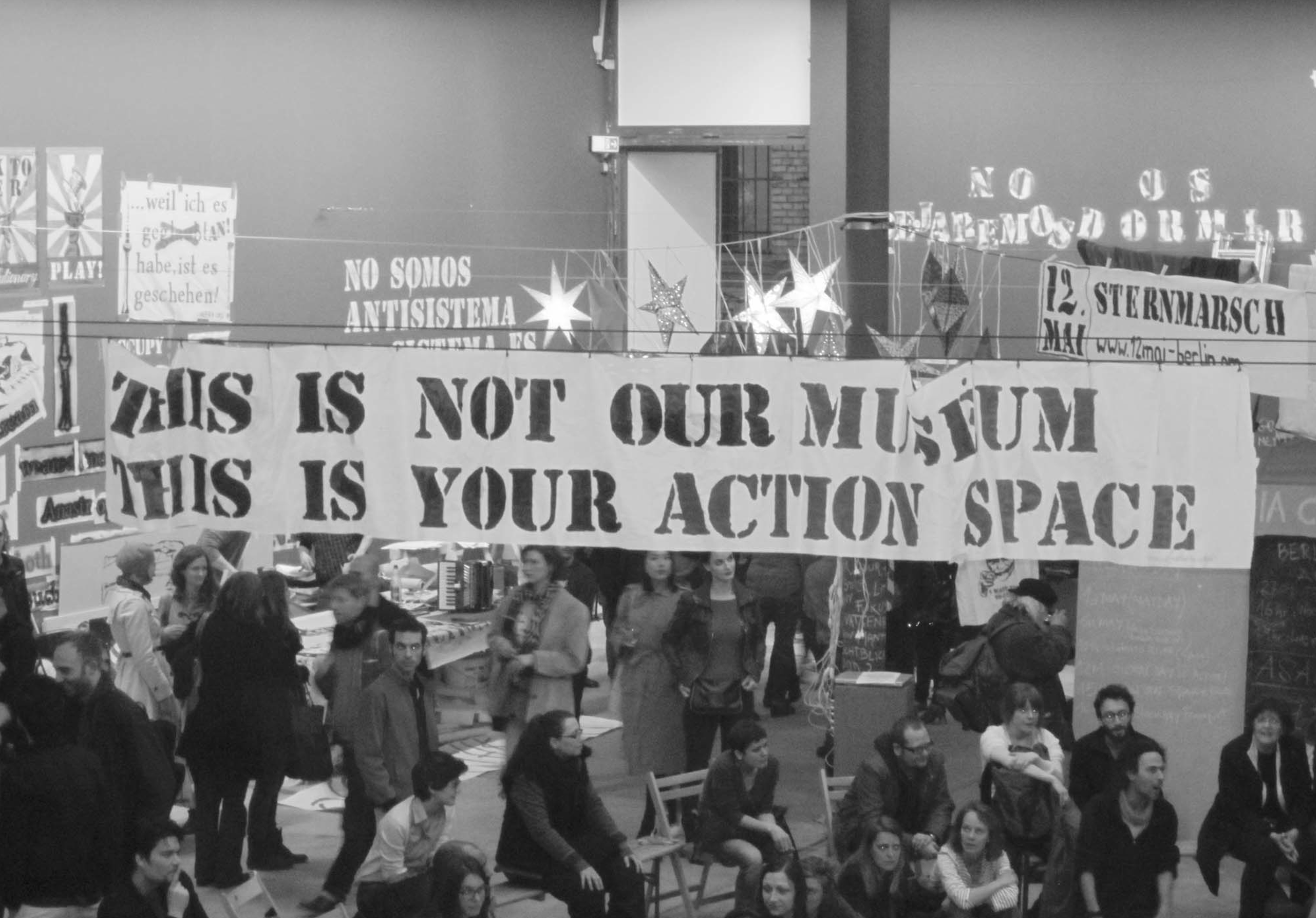

T.B. While many of our actions have been held within museum walls, Occupy Museums has been focused on criticizing prominent New York City cultural institutions from the outside. Our invitation to the Berlin Biennale was interesting to me for three reasons. First, we would be given the opportunity to meet activists from throughout Europe and work together to build a global network of activists. It has been clear to me for some time that a global crisis requires a global response, and I was looking forward to sharing ideas and tactics with our counterparts abroad. Second, although Germany is moving toward the privatized American model of arts patronage, it still has strong government support for the arts and I believe this is an important, albeit problematic, model to explore. Working within the German arts context would give us insight to a model that is in fact so different from the one in which we operate in the US. Third, the opportunity to push the boundaries of the institution from within was

interesting. The Kunst Werke, where the Biennale was held, is a good example of a common arts institution operating within a hierarchical corporate structure. But if we are to have a democratic culture, shouldn’t our cultural institutions operate democratically? Our position within the Biennale and our collaboration with the curators gave us leverage to experiment with new models and new ideas. Currently, the Biennale is in the process of horizontalizing its working structure and decisions are increasingly made by consensus within committees. This is an exciting development.